A fully programmable immune system

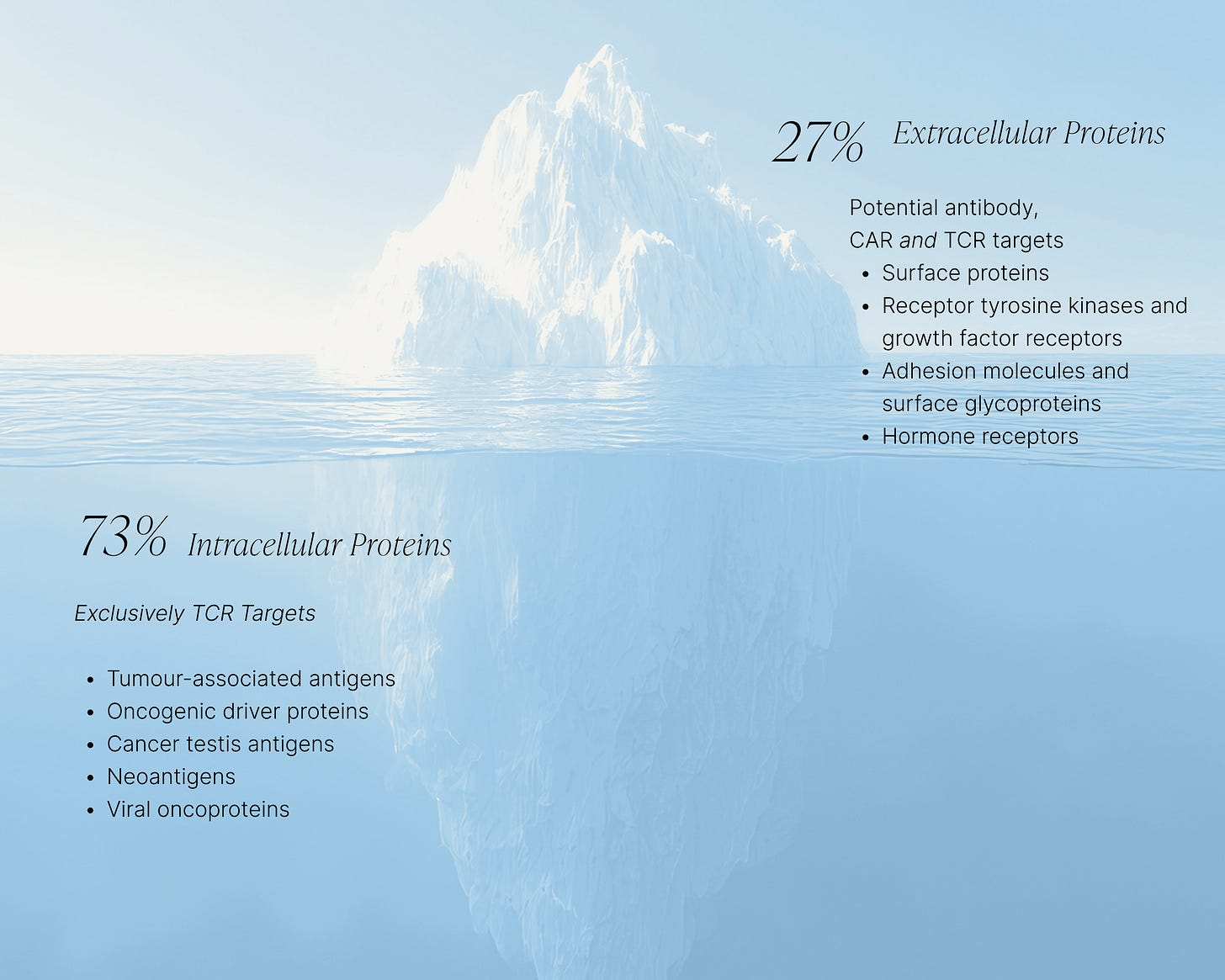

If you’ve been watching the explosion of immune therapies over the past decade, you might think we’ve already mapped the immune system’s potential. CAR-Ts, checkpoint inhibitors, antibody drugs have all changed medicine. However, we have only been fishing in the shallow end: the real ocean of opportunity lies inside the cell, and TCRs are the key to unlocking it. Unlike antibodies that can only “see” the 10–20% of proteins sitting on the cell surface, TCRs can target the other 80–90%, the intracellular world where most disease biology actually happens. This isn’t just a new class of drugs; it’s an entirely new universe of targets across oncology, virology, and autoimmunity that have been completely off-limits until now.

The beauty of TCRs is their versatility. Cancers, autoimmune conditions and infectious diseases aren’t simple but rather messy, heterogeneous, polygenic diseases. TCRs let us fight complexity with precision. Instead of one blunt therapy that only works for a fraction of patients, imagine precise cocktails of TCRs tuned to a patient’s HLA type and mutational landscape. Suddenly, “precision medicine” isn’t a marketing slogan, but a scalable reality. This flexibility makes TCRs the ultimate adaptive platform for tackling the most challenging diseases we face.

Cell therapies like TCR-Ts have already proven that this biology works, but they’re expensive to manufacture and tough to deliver safely at scale. Enter TCR T cell engagers (TCR TCE): off-the-shelf molecules that harness the body’s own T cells to do the killing. Without the need for cell factories, multi-week manufacturing cycles, we can design safe, potent, exquisitely targeted molecules that direct your native immune system to clear disease. The next wave of immune therapeutics won’t be built on the backs of cell factories, it will be built on TCRs.

This panacea is no longer theoretical: the first two clinical proof points are already here. KIMMTRAK (Immunocore’s gp100 TCR bispecific) became the first approved TCR therapy in 2022, delivering unprecedented survival benefits in metastatic uveal melanoma. TECELRA (Adaptimmune’s autologous cell therapy against MAGE-A4) was approved in 2024 for treatment of advanced synovial sarcoma, an important weapon in the fight against solid tumours. Unlike many antibody modalities, which require broader in vivo assessment of Fc functions and complex pharmacokinetics, TCR programs often advance with a more streamlined in vivo package, supporting faster and more cost-efficient progression into early clinical studies.

The field is no longer a “what if”, it’s a “now”: the science is proven, the biology validated, and the commercial white space enormous. The TCR revolution has begun, and we at Synteny are looking to define its future.

TCRs target intracellular antigens: over 70% of the proteome that is largely unaddressable by other modalities

What makes TCRs such a commercially attractive platform is that they can - in principle - target any intracellular protein. The targetable landscape is therefore much larger than it is for small molecules and antibodies, which are for the most part limited to surface-expressed proteins only.

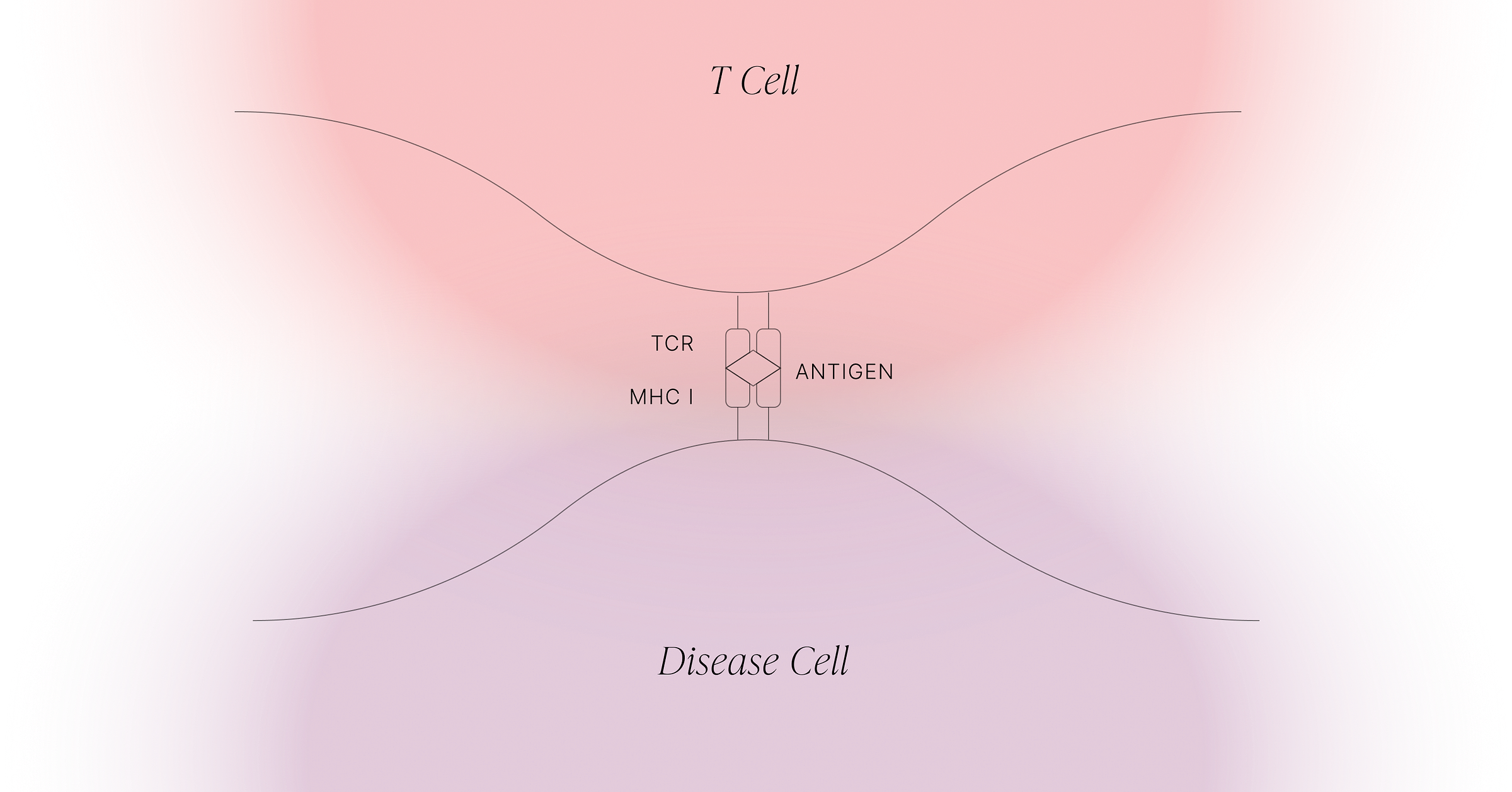

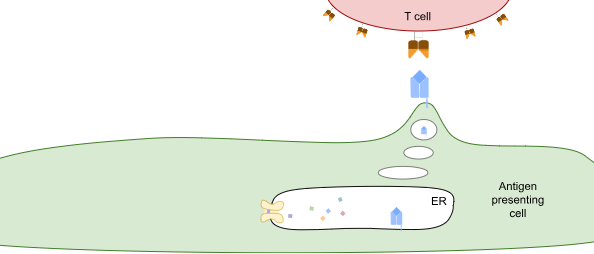

TCRs survey the intracellular proteome by exploiting what is effectively the waste-disposal system in cells. When proteins are degraded, they’re first broken down into different-length fragments, and eventually those fragments are broken down into amino acids. But along the way, some of those fragments are shuttled into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a compartment inside the cell that contains HLA class I proteins (see figure below). These HLA proteins bind to peptides and take them to the cell surface for TCRs to observe.

One of the fascinating aspects of T cell responses is that they are adaptive, as opposed to being innate, or germline-encoded. The receptors of T cells are generated randomly in the thymus, with each T cell containing one receptor. T cells are then discarded if they fail one of two checks: first, they have to be able to bind to the HLA complexes of the host which are presented by specialised cells within the thymus. This requirement is then caveated by a second requirement, that they do not bind to these thymic HLA complexes too strongly. As the thymus presents lots of HLA complexes that contain potentially millions of self peptides - peptides which derive from the host’s proteome - this ensures that any T cells that recognise a self peptide are removed. After these checks, you’re left with an army of potent immune cells that are able to bind to non-self (e.g. pathogen-derived) peptides, but shouldn’t be autoreactive.

The final piece of the puzzle, and the reason this system protects us so effectively, is the extraordinary diversity of HLA proteins. Different HLA alleles present very different sets of peptides. As a result, if a pathogen mutates its proteins to avoid binding your HLA molecules, those same mutations are unlikely to help it evade mine. At the population level, this leaves the pathogen with very little evolutionary advantage. Thus, adaptive immunity is generated somatically, giving each individual a uniquely diverse repertoire of immune receptors that are tuned to that person’s specific HLA alleles.

While HLA diversity provides population-level protection against rapidly evolving pathogens, it also introduces a major challenge for developing TCR-based therapies. Because disease states are presented differently to the immune system depending on a person’s HLA type, therapies that rely on engineered TCRs can only target a limited set of peptide–HLA complexes. The biggest commercial opportunities for TCR-based therapies are found when a disease-associated peptide is presented on a HLA allele that is commonly presented amongst a population.. The most common HLA allele in the US and EU markets is HLA-A*02, which is expressed in around 40% of individuals. Notably, both KIMMTRAK and TECELRA target the HLA-A*02-expressing subpopulation. However, HLA-A*02 is not the only allele worth considering.

At Synteny, we are focused on programming TCRs to recognise multiple HLA alleles that present the same peptides; providing an opportunity to expand the number of patients accessible with a single therapy. One example of this is combining HLA-A*11:01 and HLA-A*03:01, which have a significant overlap in the peptides they present. Owing to differences between these two HLAs, it is not usually the case that a TCR that binds to one will bind to the other. In fact, it is quite the opposite. Therefore, it becomes a protein design problem to engineer TCR sequences that are able to tolerate the differences between these HLAs, but maintain sufficient affinity and specificity to the presented peptides to be safe and effective therapies. By unifying multiple HLAs, we are able to address a larger fraction of patients.

Turning TCRs into potent therapeutics

Biologically-derived therapeutics (‘biologics’) have revolutionised drug treatment in the 40 years since their first approval, with biologics now accounting for over a third of all newly approved drugs. The drug development process for biologics offers both advantages and challenges compared to traditional small molecules. For example biologics retain many of the natural properties of the molecules they derive from, and so can remain biologically active within the body for a long time. However, they are also large and typically complex molecules, presenting challenges in how they are made, stored, and delivered into the body.

The majority of approved biologics are based on monoclonal antibodies. This technology exploits antibodies, soluble molecules produced by B cells, whose role is to identify anything ‘non-self’ and generate an immune response towards it. These naturally occurring molecules are one of the most abundant proteins in sera, providing a protective barrier against reinfection by rapidly neutralising pathogens before they have had time to establish an infection. Monoclonal antibody technology relies on identifying a B cell clone which produces an antibody that binds to a target, typically by immunising mice with a target protein of interest. Individual B cells from immunised mice are then fused with an immortalised cell derived from a myeloma, creating an immortalised cell line, known as a hybridoma, which acts as a protein production facility making large amounts of the target specific antibody.

As antibody-based biologics have grown in number, the platforms which support both identification and production have evolved in efficiency and robustness. There are now a variety of ways to identify antibody sequences that bind to a target of interest. In addition to traditional immunisation strategies using mice, a variety of in vitro and in vivo systems have been developed. For example, camelid antibodies, which have a single chain responsible for target binding instead of the 2 chains used in humans and mice, have been adapted to generate large synthetic libraries suitable for high throughput screening, increasing the speed and efficiency of target screening. Likewise the traditional process of hybridoma generation has evolved in response to technological advances in DNA sequencing and gene synthesis. Antibodies can now be rapidly sequenced, synthesised, and cloned into specialised mammalian cell systems highly optimised for producing consistent drug products at high yield.

In addition to producing high quality antibodies more quickly, modern antibody technology platforms are able to generate modular antibody-like structures, where specific antibody domains have been switched to impart multi-specificity or enhanced function. For example, a major growth area in antibody-based therapeutics is the bispecific protein, where two antibody chains with different target specificities are brought together into one therapeutic protein. A major group of antibody-based bispecifics are the T cell engagers (TCEs), where antibody-based target binding is coupled with bystander T cell engagement through binding to CD3.

Antibodies have dominated the growth in biologics due in part to their natural properties as soluble molecules. As TCRs are membrane proteins, we need to adapt their structure for use as soluble therapeutics. Conversion of TCRs into soluble proteins typically involves first removing the areas of protein which interact with the membrane, and introducing amino acids that help to stabilise the interactions between TCR chains. TCRs also do not have a direct capacity to signal to the immune system, and so solubilised TCRs require the addition of a further structure to generate a biologic effect, known as an effector function. Currently TCR-based therapeutics in the clinic function as T cell engagers (TCR-TCEs), which use a similar antibody-based effector domain to that of other TCEs, engaging bystander T cells through binding CD3.

The more than 200 antibody-based TCEs currently in clinical trials across the world offer an exciting opportunity to exploit the technological enhancements in this area in the development of TCR-based TCEs. TCRs and antibodies are structurally similar proteins, with constant and variable domains that can be interchanged with each other. This kind of modular approach has been applied to several TCR-TCEs within the clinic, that are able to be produced at scale, resolving many of the early challenges in TCR-TCE product yields, and also enable the imparting of more antibody-like properties on the molecules, such as longer biological half lifes.

TCR repertoires: a fossil record of disease

Designing individual TCRs shows the power of precise antigen recognition, but these receptors sit within a vastly larger and more complex ecosystem. Understanding that ecosystem requires looking at entire TCR repertoires. A TCR repertoire is essentially a census of the T cells present in a biological sample. In practice, this is usually measured by multiplex PCR amplification of rearranged TCR genes, most commonly the β chain, followed by high-throughput sequencing. The approach is inexpensive, scalable, and does not require any knowledge of antigen specificity: it simply returns the set of TCR sequences present in the blood or tissue at the time of sampling. Classical repertoire sequencing captures single chains, but new methods are beginning to link α–β pairs in bulk (for example, TIRTL-seq), allowing more complete characterisation of the receptors present in a sample without the cost or complexity of single-cell sequencing.

A typical repertoire survey generates 10,000–1,000,000 unique TCR sequences per person. Because TCR generation is a deeply stochastic process, most sequences are “private”: they are unique to an individual or present in very few people. Consequently, every new person sampled adds tens of thousands of previously unseen data points. This has created a rare situation in immunology where large datasets, tens of thousands of individuals, can be built cheaply, with each sample providing new and informative sequence diversity.

Why does this matter?

Even in their unlabelled form (i.e. without knowing what antigen they recognise), repertoires provide an extraordinarily rich corpus for learning the underlying “grammar” of TCRs. From an AI perspective, this is an ideal training domain: billions of real biological sequences shaped by evolution and tolerance, but without task-specific labels that might bias or limit the space of solutions. Models trained on these data can learn the latent structure of TCRs, motifs, constraints, allowed rearrangements, biophysical preferences, and use this foundation to predict antigen binding or generate new TCRs with desired properties.

Large case–control studies add another powerful layer. By comparing the repertoires of people with and without a disease, it is possible to identify specific TCR sequences associated with that condition, an approach exemplified by the landmark Emerson et al. (2017) study in Nature Genetics. Many autoimmune diseases have now been shown to harbour “public” pathogenic TCRs that are enriched across patients. The key limitation, until recently, has been that we typically do not know what these disease-associated receptors bind.

This is where a working TCR–antigen model and high-throughput mapping technologies become essential. If we can de-orphan pathogenic TCRs, linking sequence to antigen using in silico prediction or in vitro platforms such as large-scale signalling pMHC libraries, we can finally identify the causal antigens driving autoimmune pathology. For diseases like ankylosing spondylitis, type 1 diabetes, and others with strong immunogenetic signatures, this offers a route to discovering previously unrecognised therapeutic targets and, ultimately, new ways to intervene upstream of tissue damage.

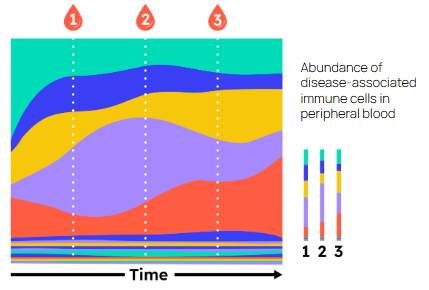

Towards disease diagnosis from repertoires

Looking ahead, the ability to infer antigen specificity directly from sequence unlocks a much broader opportunity: using repertoire sequencing as a diagnostic test. Today, repertoire surveys are cheap, fast, and widely deployable, but limited by the fact that almost all TCRs are “orphans.” As models improve, we will be able to annotate increasing fractions of a repertoire with predicted antigen targets and immunological context. This creates a path to diagnosing hard-to-detect diseases, especially autoimmune conditions, where the pathogenic clones are often abundant in blood, potentially even to early cancer detection, where tumour-associated T cells circulate long before imaging or symptoms emerge.

In this future, a simple, low-cost repertoire assay could become a powerful screening tool: a snapshot of the adaptive immune system that reveals which diseases the immune system is currently responding to, or about to respond to. With the combination of large population-scale repertoires, accurate TCR–antigen models, and scalable wet-lab mapping, this is rapidly moving from aspiration to reality.

Learning the laws of TCR-antigen recognition: a problem perfectly suited to AI

The versatility that makes TCRs so attractive as a diagnostic tool and a therapeutic modality also makes them hard to engineer using lab-based or traditional computational methods. A functional repertoire spans ~10¹⁵ possibilities, and current discovery methods such as screening donor blood, panning for binders, or affinity-maturing individual clones, only ever sample an infinitesimal corner of that space. Unlike small molecules, there is no TCR counterpart to fragment-based heuristics: amino acid motifs in TCRs are almost completely uninformative when removed from their global structural and sequence context.

Combinatorial explosion used to be the standard argument against applying AI to biological design. That view has not survived the past decade. AlphaGo, image generation, and ultimately with language models operating across endless combinations of tokens have shown that scale and complexity are no longer blockers. In protein engineering, AI approaches have breached the domain of antibody design and TCRs sit squarely in the crosshairs of this space where generative AI and AI-led discovery excel. For example, we at Synteny have shown that, given appropriate data, TCR affinity programming is directly accessible as a statistical inference problem.

But TCR therapies demand much more than discovering single target binding: balancing self-tolerance with potency, engineering cross-HLA recognition, and tuning multi-antigen binding while avoiding off-targets. These are essentially multi-objective challenges and are not screenable at scale. They are, however, exactly the kinds of conditional optimisation problems that modern generative and probabilistic models are designed to solve.

Indeed one could even make the argument that every question in TCR drug discovery and diagnostics can be expressed as a conditional probability over biological sequences and relevant property-encoding random variables. What does this receptor bind? How do I change it while preserving binding to this antigen? What is the likelihood of cross-reactivity? These map naturally onto modern probabilistic and generative AI frameworks.

Taken together, frontier biology and frontier AI render TCR design tractable and open an entirely new window into programmable biology.