Inference Time Control of Diffusion Models in Drug Discovery

Drug discovery can be viewed as a constrained statistical sampling problem. Like composing a sentence, designing molecules and protein sequences demands precise control over both semantics and syntax. The semantics include properties such as target binding affinity, solubility, and chain stability, while the syntax refers to the identities and arrangement of atoms or amino acid residues.

In late 2016, amid rising excitement around deep learning in vision and speech, a preprint by Gómez-Bombarelli et al [1] quietly made a breakthrough that marked a turning point for drug discovery. The authors introduced a variational autoencoder (VAE) capable of generating molecular structures – not pixelated reconstructions of faces, but chemically valid graphs of atoms and bonds. This was more than a technical novelty. It opened the door to continuous latent spaces that could be sampled and decoded into tangible drug candidates.

While the VAE (and also concurrent developments with recurrent neural networks [2]) marked the genesis of deep generative chemistry, a more recent major inflection point is score-based generative modelling. First applied in drug discovery contexts in a brace of papers just two years ago [3, 4], these diffusion models offered a rather different approach to generation by learning to reverse a modeller-scheduled forward stochastic process that gradually adds noise to data, eventually learning to reconstruct structured objects like molecules or proteins from pure noise. Their enduring popularity (over, say, language modelling approaches) stems from the ability to steer the generation towards many different constraints.

Why syntactic constraints matter

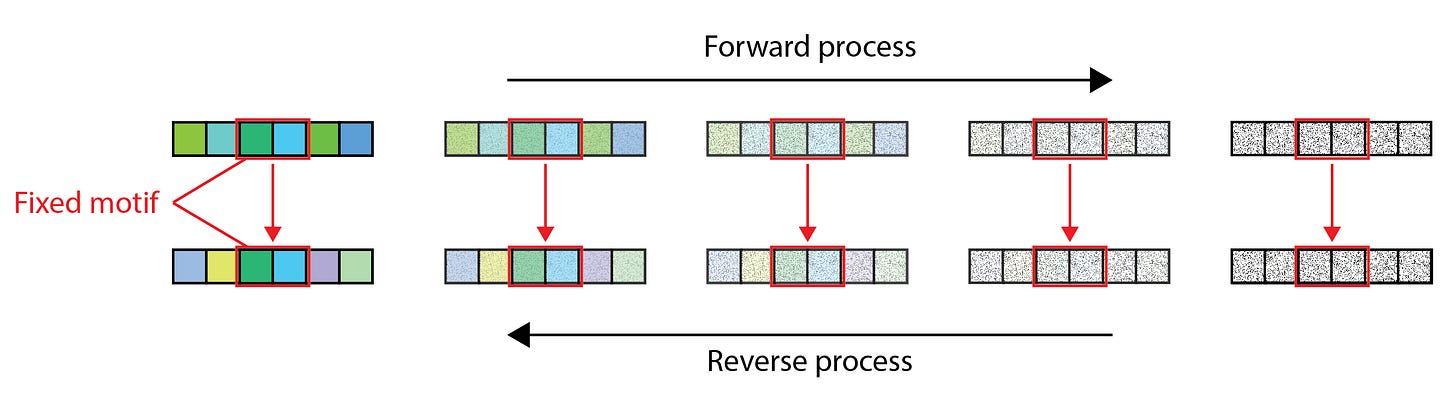

While de novo generation in drug design may be the approach du jour, many practical applications benefit more from completing or modifying existing sequences in reliable, property-preserving ways. Grafting, or scaffolding, motifs, redesigning CDR loops in antibodies and T cell receptors (TCR), or mutating just a single residue at a late design stage — these are all special cases of inpainting, a familiar task in the image processing domain. One of the earliest approaches to inpainting, which is often called replacement sampling, involves evaluating the diffusion gradient function at each denoising timestep with the values of the fixed data dimensions replaced with the corresponding noised target values of the forward process. We illustrate this process in Figure 1 below.

The pitfalls of naive sampling

Despite its simplicity, replacement sampling suffers from the foundational flaw that the sampled distributions are not actually the reverse of any valid forward diffusion process. This is not merely a technicality. For instance, the replacement sampling distribution introduces an irreducible approximation error [5, 6] that persists even with larger models and ever greater sampling steps.

For many applications, particularly in vision, this limitation is sometimes tolerated. Methods like RePaint [7] have built upon replacement sampling with iterative noise-cut-paste schemes, delivering striking improvements in visual fidelity. But drug discovery demands more than perceptual realism.

To illustrate the problem, consider the following toy experiment.

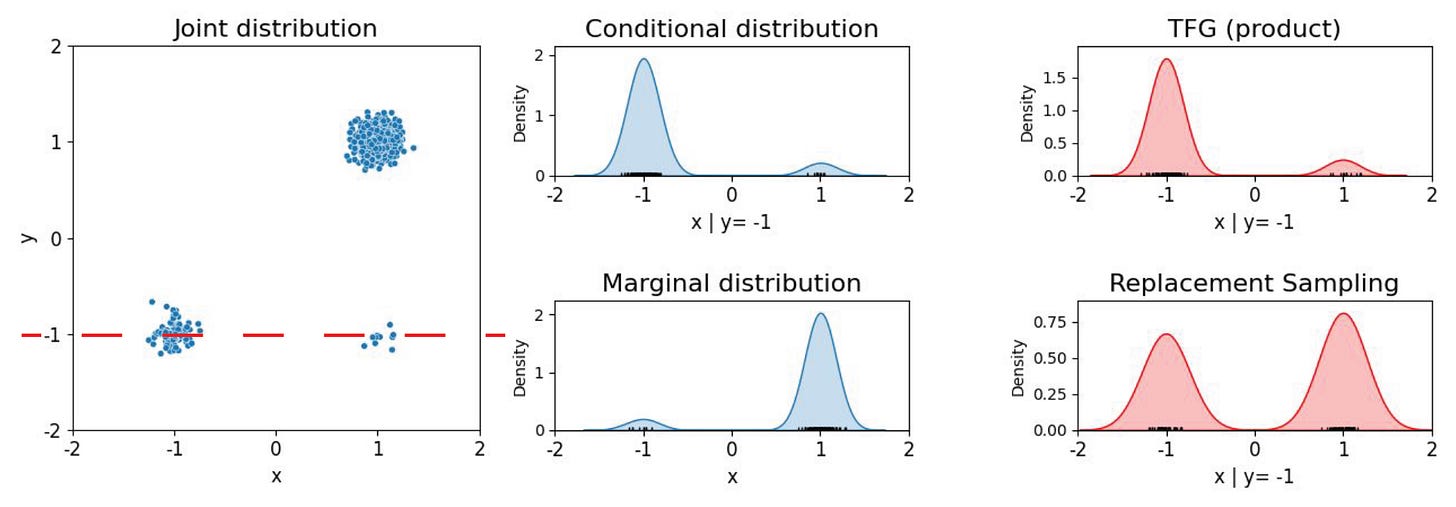

Say we have the task of sampling points on a map of the world according to human population density. Here we mock up such a toy population map by sampling from an imbalanced mixture of three 2D Gaussians to produce a synthetic dataset as shown in Figure 2 below.

We then train a (tiny) diffusion model to recover this joint distribution. If we were to then limit our sampling to the longitude by fixing the latitude to the lower value, this is essentially the task of inpainting the x-coordinate around a fixed y-coordinate (y=−1). Under correct conditional sampling, the sampled data should lie predominantly within the bottom left area where the probability mass is concentrated. However with replacement sampling, the model is driven toward the overall data mode, as we see above. It fills in data from the bottom right region, largely ignoring the conditional, because that is where the density is highest under the marginal. No increase in the number of diffusion sampling steps can correct this flaw.

This simple failure mode serves up a caution for drug design. When the conditional diverges significantly from the marginal, as it often does in real-world biology, inexact sampling tends to snap back to dataset priors. In TCR sequence design, for instance, publicly available datasets are heavily skewed toward viral antigens. Without proper treatment, generated sequences meant to bind cancer neoantigens, say, will drift toward the viral-antigen associated sequences that dominate the training data. The consequences go deeper than isolated residue mis-sampling as global effects come into play, such as altered epitope specificity, or poly-specificity [8], thereby exposing one to latent off-target binding risks.

Moving beyond heuristics to exact conditional sampling

These pitfalls have been met with a large number of innovative solutions in recent years. Here we highlight one class of methods that eschew approximations — such as the pairing of ancestral sampling with heuristic substitutions, or variational inference methods — for asymptotically exact sampling [5, 9, 10]. This is arguably an attractive strategy in domains that value fidelity over inference speed.

Because each intermediate distribution gently interpolates between the pure noise and the sharp conditional (posterior), we should be able to guide the sampling process using well-established Monte Carlo sampling techniques defined for sequences of annealed distributions that end on the posterior. These approaches are now at the heart of many modern protein generative models [11].

Training-free generalisations

But the powerful consequences of this framework is not restricted to its correctness but also its generality and efficiency.

As we show if one defines the intermediate distributions as products of the form

where the original label points to the prior reverse process distributions whose gradients are learnt during (unconstrained) diffusion model training and the second term a conditional forcing term, then provided they anneal to the posterior at the end of the diffusion process, there is no restriction on the form of the conditional distribution itself. This freedom unlocks a far richer class of other applications. For instance, it can be a delta function fixing a motif, like in inpainting, a soft constraint like sequence similarity, individual residue scores for biophysical heuristics such as solubility, residue-pair scores for protein stability, or indeed a theoretically infinite variety of conditions through combinations of distributions, all from a single trained model without the need for individual task-specific conditional training.

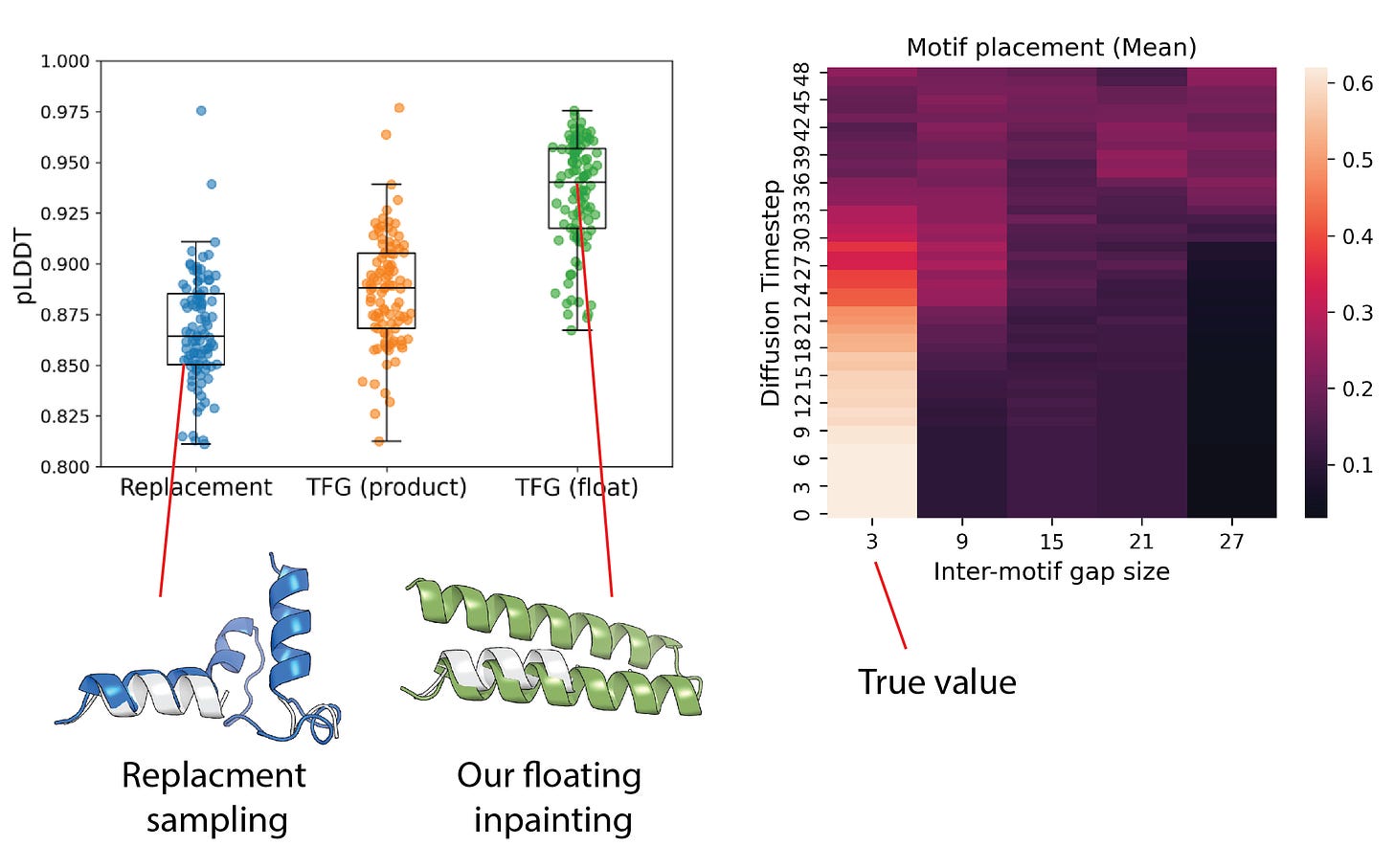

Example: Scaffolding Without Positional Fixing

Structure scaffolding is a common design pattern in protein engineering where one fixes the atomic coordinates of a desired functional motif (e.g. a set of helices) or an interacting region (e.g. an antibody loop or enzymatic site), and seeks to scaffold a full protein backbone around it. Traditional methods require the user to predefine the number of residues between fixed motifs, introducing brittleness and human bias. Prior work such as Floating Anchor Diffusion Models [12] introduced motif flexibility into the generative process but requires specialised training procedures tailored to that objective. By contrast, our method introduces no additional retraining burden [6]. Under the training-free guidance framework, we define the conditional forcing term as a mixture distribution across a range of inter-motif lengths. The model learns to scaffold both motif placement and the surrounding structure during sampling.

We demonstrate this using RFdiffusion [3] as the base model, taking care to exclude task-specific components. Unlike replacement sampling, which requires the user to specify the number of intervening residues, our scaffolds not only achieve higher fold success rates, but also recover the correct motif spacing automatically in a single shot, reducing the risk of poor folding through misspecified positioning. We show this below for a simple scaffolding task around a discontinuous motif where the model correctly picks the correct spacing midway through the set of intermediate distributions, leading to high-confidence resulting structures.

References

[1] Gómez-Bombarelli, Rafael, et al. “Automatic chemical design using a data-driven continuous representation of molecules.” ACS central science 4.2 (2018): 268-276.

[2] Segler, Marwin HS, et al. “Generating focused molecule libraries for drug discovery with recurrent neural networks.” ACS central science 4.1 (2018): 120-131.

[3] Watson, Joseph L., et al. “De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion.” Nature 620.7976 (2023): 1089-1100.

[4] Ingraham, John B., et al. “Illuminating protein space with a programmable generative model.” Nature 623.7989 (2023): 1070-1078.

[5] Trippe, Brian L., et al. “Diffusion probabilistic modeling of protein backbones in 3d for the motif-scaffolding problem.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.04119 (2022).

[6] Cornwall, Lewis, et al. “Training-Free Guidance with Applications to Protein Engineering.” NeurIPS 2024 Workshop on AI for New Drug Modalities.

[7] Lugmayr, Andreas, et al. “Repaint: Inpainting using denoising diffusion probabilistic models.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2022.

[8] Karthikeyan, Dhuvarakesh, et al. “Conditional generation of real antigen-specific T cell receptor sequences.” Nature Machine Intelligence (2025): 1-16.

[9] Cardoso, Gabriel, et al. “Monte Carlo guided diffusion for Bayesian linear inverse problems.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.07983 (2023).

[10] Wu, Luhuan, et al. “Practical and asymptotically exact conditional sampling in diffusion models.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2023): 31372-31403.

[11] Wohlwend, Jeremy, et al. “Boltz-1 democratizing biomolecular interaction modeling.” BioRxiv (2025): 2024-11.

[12] Liu, Ke, et al. “Floating anchor diffusion model for multi-motif scaffolding.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.03141 (2024).